Few would argue the necessity of professional learning in the education space. From classroom teachers to school leaders to district administrators, we all have identified areas of growth in our professional practice. But there is some debate about the ‘how’ – whether educators should rely on experts to lead their professional development or lean into the knowledge and experience of colleagues. While there isn’t one right answer for every circumstance, it is generally agreed upon that the ‘stand and deliver’ model is as antiquated in the professional learning context as it is in the classroom.

To increase your teams’ engagement in and ownership over professional learning, consider establishing Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) at your school or district.

What is a Professional Learning Community (PLC)?

A Professional Learning Community is a group of three to five people who are engaged around a common problem of practice to identify solutions, put them into practice, assess their efficacy, and iterate as necessary. PLCs can exist at any level within a school system – from classroom teachers to district leadership – that is bound by the commonality of their work.

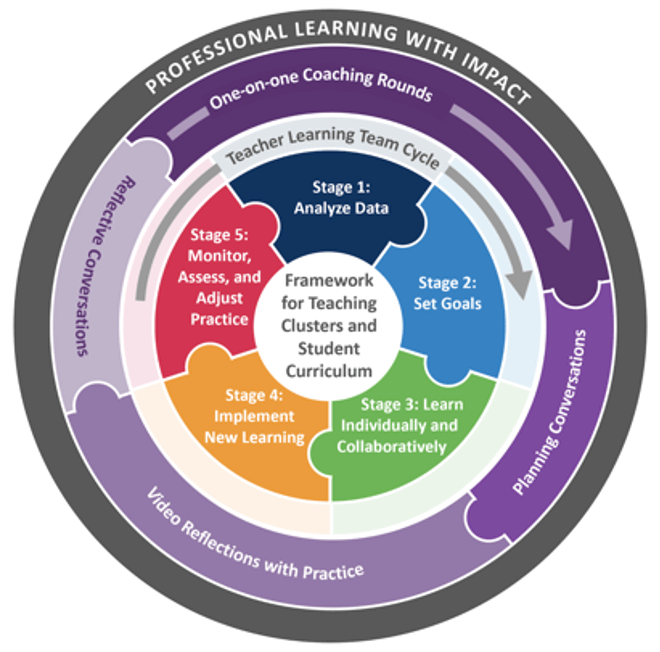

PLCs engage in a cycle of inquiry around a specific problem that is identified by analyzing data and identifying the root cause of that problem. For example, if an interim assessment identifies that children are struggling with vocabulary, we know there is likely not enough discussion in the classroom. A PLC would set goals for increasing discussion, research, and share knowledge about effective practices in classroom discussion, implement new solutions, and assess and iterate as the group works towards its goals.

Inquiry cycles – from data analysis through monitoring and adjusting practice – should be between six and nine weeks and are often bounded by the availability of new data, such as interim assessments.

What Principles Should Guide a PLC?

1. Shared ownership

A PLC is not a passive form of professional development where participants are hearing from experts. The responsibility and ownership for the group is shared, without hierarchy among the group. The focus should be on collective agency, self-regulation, knowledge sharing, and building trusting relationships.

2. Anchored

A PLC must be anchored in a shared vision of instructional excellence and student success. This could be a chosen curriculum, research, or instructional model such as the Framework for Teaching. Having this anchor will allow participants to have a common language and reference point for their inquiry.

3. Learner-Centered

A PLC should be learner-centered in that the learning opportunities attend to the whole person, with particular consideration given to the cognitive, social, and emotional needs of the participant. Doing so will allow participants to feel safe and be vulnerable during the learning process.

4. Symmetrical

Effective professional learning should be symmetrical to the student learning environment, with adult participants doing the heavy lifting in the PLC just as we expect students to in the classroom. The PLC should be highly collaborative, with participants engaging in problem-solving and deeper learning, and the skills and mindsets that we seek to develop in students should be modeled in the PLC.

To be successful, PLCs need mutual trust among participants and protected time to engage. In a school or district, this is a unique opportunity to build cross-functional collaboration amongst professionals in different roles, allowing teams to interact in ways that traditional planning and professional development may not allow.

Now more than ever, educators need opportunities to collaborate and learn from each other as remote and hybrid learning models have required innovation from everyone within a school and district community. Professional Learning Communities are a proven practice improvement strategy that can establish a culture of inquiry, continuous improvement, and trust among your team, and ultimately lead to better outcomes for students and higher levels of satisfaction from educators.

This blog was originally published on The Danielson Group’s blog. It has been republished here with permission.