Rebranding the Library

In an effort to defy the restrictive, historical caricature of libraries as venues where talking, eating, and personal electronic use is prohibited, I decided to rebrand the stereotypical perception of a school library to one that promotes louder-than-a-whisper discourse and constant collaboration. As a teacher-librarian (TL), I see myself as a teacher first and a librarian second, just as my title is listed. For me, the library is my giant classroom where I try to create a student-centered, resource and language rich environment. For this reason, I tore down all my “no” signage, created collaborative seating arrangements to encourage discussion, and even sponsored a library logo design contest for the students. More importantly, I redesigned lessons to make questions — not answers — the primary focus.

Students Having a Discussion — in the Library

In the past, patrons would go to libraries because they sought answers to their questions, but today, answers are easy; just Google it, right? What I have noticed when working with students is that they struggle to formulate relevant questions with depth. The struggle is real because it’s rooted in a fear of feeling stupid and insecure, especially in front of peers. With the proliferation of “fake news” and “alternative facts,” libraries must rebrand themselves as facilitators of inquiry to scrutinize the “answers,” cultivate the courage to challenge, and promote intellectual curiosity.

Tapping into Your School Library

In many schools, the library is an untapped resource. When a school library is well stocked with current, relevant resources, any topic is open for exploration and discussion. For this reason, my role is to encourage students to pursue their personal and academic interests, passions, and curiosities. As a TL, I strive to be aware of the most current, user-friendly resources, teaching strategies and pedagogy, and educational technology so that I can position myself as an educational leader on campus. What invigorates me is trying new things and I want to inspire students to do the same. I try to be a role model for experimentation and learning from mistakes. When students see my willingness to try new things, it encourages that same adventurous spirit in them.

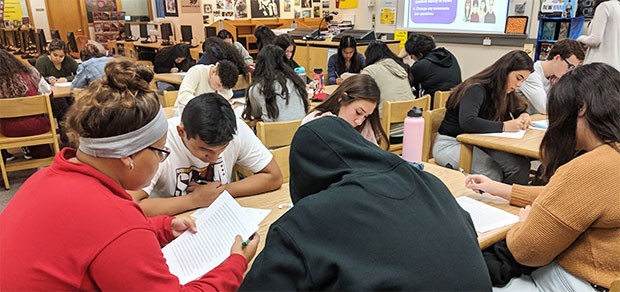

Consequently, the library becomes a sanctuary for non-judgmental interaction between adults and young adults. As restrictive as libraries are perceived, ironically, they provide the most freedom for young adults to cultivate — and in many ways design — their own approach to learning. Whenever I collaborate with classroom teachers on lessons, I always allow for student choice and flexibility. I even encourage students to challenge the task and suggest other approaches. No matter what the purpose is for class visits to the library, my emphasis is always on collaboration and metacognition. Under the stewardship of a highly qualified teacher-librarian, school libraries provide instructional, academic, technical, and even emotional support to both staff and students.

Students Collaborating on Posters

QFTing for TLs: Discovering the Question Formulation Technique

Last fall, I attended a conference where Glen Warren talked about inquiry in the library and introduced the Question Formulation Technique (QFT). Warren mentioned that he regularly asks students, “What questions have you created?” And boom — I thought, “I never ask students about their questions because the questions are always already provided.” The typical role of the TL has been to enter the research process midway to support students in finding reliable resources, relevant answers, and citations. However, the QFT invites TLs to be involved in the critical, inquiry portion of research. Instead of helping students find the answers to a question, the QFT allows TLs to guide students while they formulate questions they care about. The QFT underscores the learning opportunities and relationship building present when a TL helps students create, revise, and prioritize their research questions. Thus, the research process becomes more authentic, rather than a scavenger hunt.

Aside from the collaborative nature of the QFT, it also allows for a full swoop of language engagement. With its understandable rules, all students, no matter their skill or language level, feel safe to share free from criticism. Any time I try a new technique or strategy, I’m mindful of the nearly 1,800 Oxnard High School students that speak a home language other than English and just over 400 students that live below the poverty line. When students enter an academic setting — especially the library, where reading is core — they carry varying insecurities; having concrete rules that allow for differentiation increases participation and confidence. Furthermore, when students share out loud, they are building vocabulary without even realizing.

Every QFocus requires a form of reading. Even if the QFocus is visual, it still requires scanning, interpreting, and noticing aspects of the visual that will inspire a question. By eliminating labels such as “bad” or “good,” students spend more time discussing their rationale, revising, and prioritizing their questions. Because it only requires a day of instruction to implement, some may think that the QFT does not demand the rigor of other strategies, but really, the entire technique touches on analysis, synthesis, and evaluation in a natural and meaningful way. What I love most about the QFT is that students don’t even realize the challenging brain work they’re doing.

Read more about two of Jenn’s full lessons here and here, and visit her resource page and QFocus bank, developed with colleagues from Oxnard High School.

Conclusion

One of the reasons that I became a teacher-librarian is because I believed in my talent as a teacher. In the library, I gain a broader reach by co-teaching with educators across all disciplines, which provides me with the unique view of seeing students improve their critical thinking skills, communication skills, and language application over multiple-use and multiple-subject areas. I feel that the QFT has allowed me to provide a bridge between required learning and desired learning. After every QFT, I have witnessed all students engrossed and feeling successful. Teachers and I saw students who never speak share, and students who are “behavior problems” cheer on others to get involved. The QFT has provided a simple, yet dynamic way to help me reestablish the library’s relevance with both the students and the teachers — both school library patrons.

Erick Garcia, an English language development (ELD) teacher, shared, “ The QFT helps my ELL students question and achieve a deeper understanding about subject-specific concepts, while developing academic language skills.” Kris Roberts, who teaches English, AVID, and journalism for publication sees the library as, “above all a safe place for students and staff to ask questions.” She points to the value of having “a space, and the person who runs it, that allows students the confidence to go out on a limb. Focus truly does become content rather than merely format.” A bonus to this practice is that students also recognize the library as an environment that validates and accepts everyone’s ability. Not only am I supporting students academically, but I’m also teaching them about themselves and the world they live in through the questions they create.

The QFT as a learning strategy has bolstered my conviction of the power of inquiry and collaboration and that rebranding for libraries is possible. Not only do I believe that school libraries offer opportunities to enhance course curriculum, provide social and emotional support, but additionally, I’m convinced it’s more important for libraries to find their place and anchor their role in the inquiry process.