As teachers, we know that connection is key to success in schools. In The Guide for White Women Who Teach Black Boys, psychologist Howard Stevenson writes about a mighty act of connection that his theater teacher performed when she came into his small, predominantly White, southern Delaware high school and declared that rather than Hello, Dolly — the play they regularly performed — that year they would perform Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun.

Nine Black students in the school — who had spent years working backstage — were front and center, connected to the theater program, to the school, to the community, through their roles on stage in the sold-out play. As a White woman, the teacher interrupted racial norms to ask, “When do Black students and Black stories get to be central to the life of this community the way White students and White stories are?” And she used her power to create possibilities for connection.

We know connection matters. We make elaborate efforts each September to get to know our students personally, to help them feel seen. We know our relationships with kids help them feel invested in their school community. But connecting for success is not only about building relationships on the individual level, but also about acknowledging our roles as gatekeepers — as people who establish and maintain the structures of school that promote connection or disengagement. Part of our role as educators is to help students connect with one another, to connect with the material, and to connect with school.

Connecting is about recognizing the ways that honors classes and magnet high schools tend to become the province of White and Asian American students, such that Whiteness and Asianness tend to become associated with “school smarts,” while Blackness and Latinoness tend to become associated with special education and vocational programs. Connecting is sometimes about disconnecting those typical associations.

Personal Story: Marguerite Penick-Parks

When I think back to my time as a White female teacher in a predominately Black high school, the most important thing I learned was to listen, to be humble, and to be ready to be surprised — or rather, to seek out surprises, because the surprises come from a jolt in the direction away from those typical associations.

I remember one young man named Michael. Michael joined my drama class a week into the school year because his family moved right after the first week of school. He obviously didn’t quite fit in. He had high-rise polyester pants. The other students said he had “nappy hair” and “Goodwill” clothes. He seemed to be not very “with it.” He used short sentences, didn’t talk much, and seemed not to understand when I’d explain things in class. He’d come up to ask me a lot of questions afterward.

One day, we were doing oral interpretations and it came time for him to perform. You could hear the snickering. I was sitting in the back as a means of discipline. He rose to speak, opened his mouth, and he had the most beautiful baritone voice I’d ever heard. I could hear the student sitting in front me say, “Whoa.” Michael just blew the class away. This beautiful oration came out of his mouth — and caught us by surprise. And he went on to join our forensics team and win every forensics competition in which he competed.

I’d stereotyped him based on a whole bunch of preconceived notions. And students had stereotyped him based on many of the same misconceptions. They were Black like him, but that doesn’t mean they were immune to the narrative that said what boys “like him” were capable and incapable of. And I remember feeling so badly about what I’d thought about him before he’d opened his mouth that day — how easy it had been to write him off because he fit the narrative I’d been fed about Black boys.

Connecting is about looking at the structures of learning that were not built for Black boys and finding a way to make them work. If students aren’t connecting with school or with us, it’s our responsibility as the adults in the relationship to find out why.

We regularly ask students to code switch with regard to language, cultural styles, dress, volume — in order to succeed in schools. Connecting students with school and school success means changing the code so that students don’t have to change themselves in fundamental ways in order to feel belonging and connection.

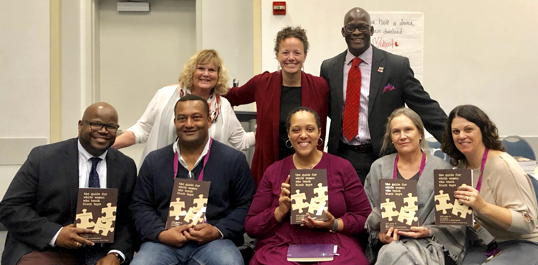

In The Guide for White Women Who Teach Black Boys, more than eighty contributors write about how to do this. Teachers, parents, students, historians, sociologists, and psychologists contributed to this volume to help White teachers of Black children understand how to connect. We invite you to check out our other two blogs from this back-to-school season, work through the exercises below — both of which were excerpted from the book — and check out our videos online.

Activities from Part Three of The Guide for White Women Who Teach Black Boys: Connecting

-

Follow the Ten Steps of an Equitable Classroom Program as recommended by Brian Johnson (Chapter 35).

- Identify criteria you will use to select students to target in the program. Johnson recommends focusing on students “in the middle of the achievement range, who typically do not have an IEP or giftedness resources” (313). Base your criteria on student goals (i.e.; academic, social-emotional support, need for individual attention).

- Identify students whom you want to include. Focus on students who aren’t meeting their potential.

- Involve parents.

- Survey the identified students, their parents, and their teachers about their experiences of school, homework, effort, behavior, and achievement.

- Review the data.

- Receive the feedback.

- Create strategies and interventions to address student challenges.

- Meet weekly with students.

- Assess your interventions and strategies.

- Rotate students out of Equitable Classrooms if they are meeting the goals.

- Create a folder for one African American boy in your class. Include information on the student’s:

-

Family life.

-

Racial, ethnic, and cultural background.

-

Languages spoken (include Black English as a language, if relevant).

-

Favorite books, music, and other interests and activities.

Then use this information to revise or design a lesson with this student in mind. Don’t tell him what you’re doing, but note the impact. As you’re able to, create more student folders and use them to influence lessons and even assessment design. When relevant, let students know how their background, experiences, and interests are central to your design of the curriculum. Ask them if it makes a difference, and, if it does, how so? (Chapter 42, Marie Michael)